When I began this Substack column, I did not realize how often I would have to respond to current events. It’s happened yet again, and I am interrupting my analysis of the “Thunderbolts” movie to reflect on the passing of yet another important comics professional of my generation, Jim Shooter, editor in chief of Marvel Comics in the 1980s. A word that keeps recurring in comics professionals’ posts about him is “complicated,” justly so. His reign as Marvel’s editor in chief was controversial, but that, I feel, is a topic for another day. Right now I prefer to focus on the brilliant beginnings of his long career in comics.

Paradoxically, Jim Shooter and I are members of the same generation, and yet he is one of the writers whose comics I read when I was growing up. That’s because Shooter started in comics at an astonishingly young age. When he was only thirteen years old, in 1965, he wrote and drew “Legion of Super-Heroes” stories and submitted them to Mort Weisinger, the editor of the Superman line of DC comics, including the “Legion” stories in “Adventure Comics.” Weisinger was impressed, and invited Shooter to come visit him in the DC offices in New York. So it was that in 1966, at the age of 14, Shooter began writing and selling stories to DC for Weisinger’s “Action Comics,” starring Superman and Supergirl, and “Adventure Comics” with the Legion of Super-Heroes. Shooter became one of the leading writers in the Legion’s long history.

Even though Shooter started at DC, he was a great admirer of the Marvel Revolution that Stan Lee and his collaborators were creating in the 1960s. Shooter was a success at DC because he applied what he learned from studying Marvel comics to writing DC characters.

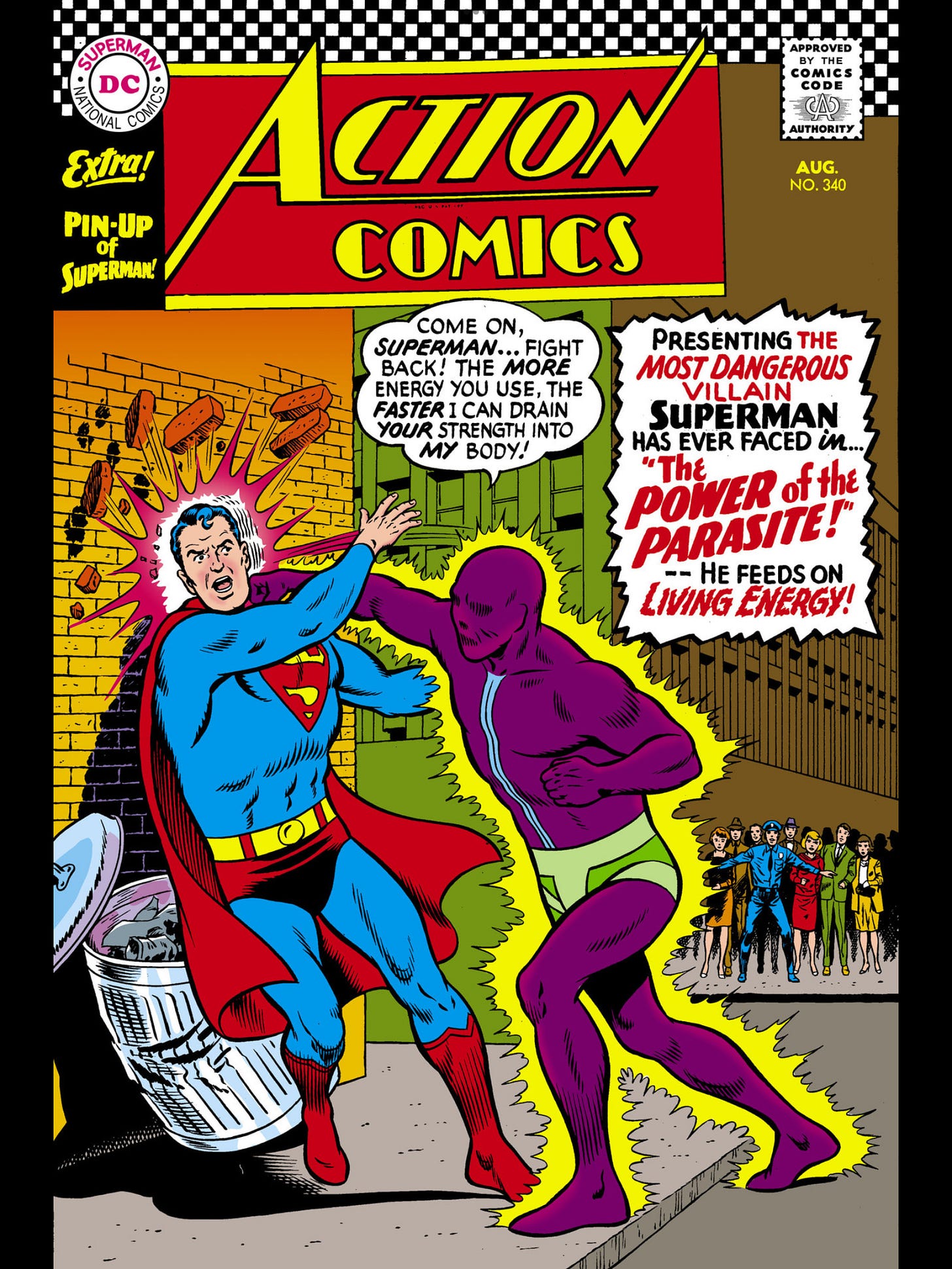

The first story by Shooter that impressed me was the Superman story “The Power of the Parasite,” drawn by Al Plastino, in “Action Comics” #346, cover-dated August 1966. This was the first year that Shooter’s stories began appearing in print. There were no credits in that issue; it was Marvel that pioneered credits for writers and artists in the 1960s. But even as a fourteen year old myself, I could tell that there was something different about this Superman story, something more dynamic than the usual run of Weisinger-edited superhero tales. Even the title of the story sounded like the kind of title Stan Lee would give a Marvel superhero story.

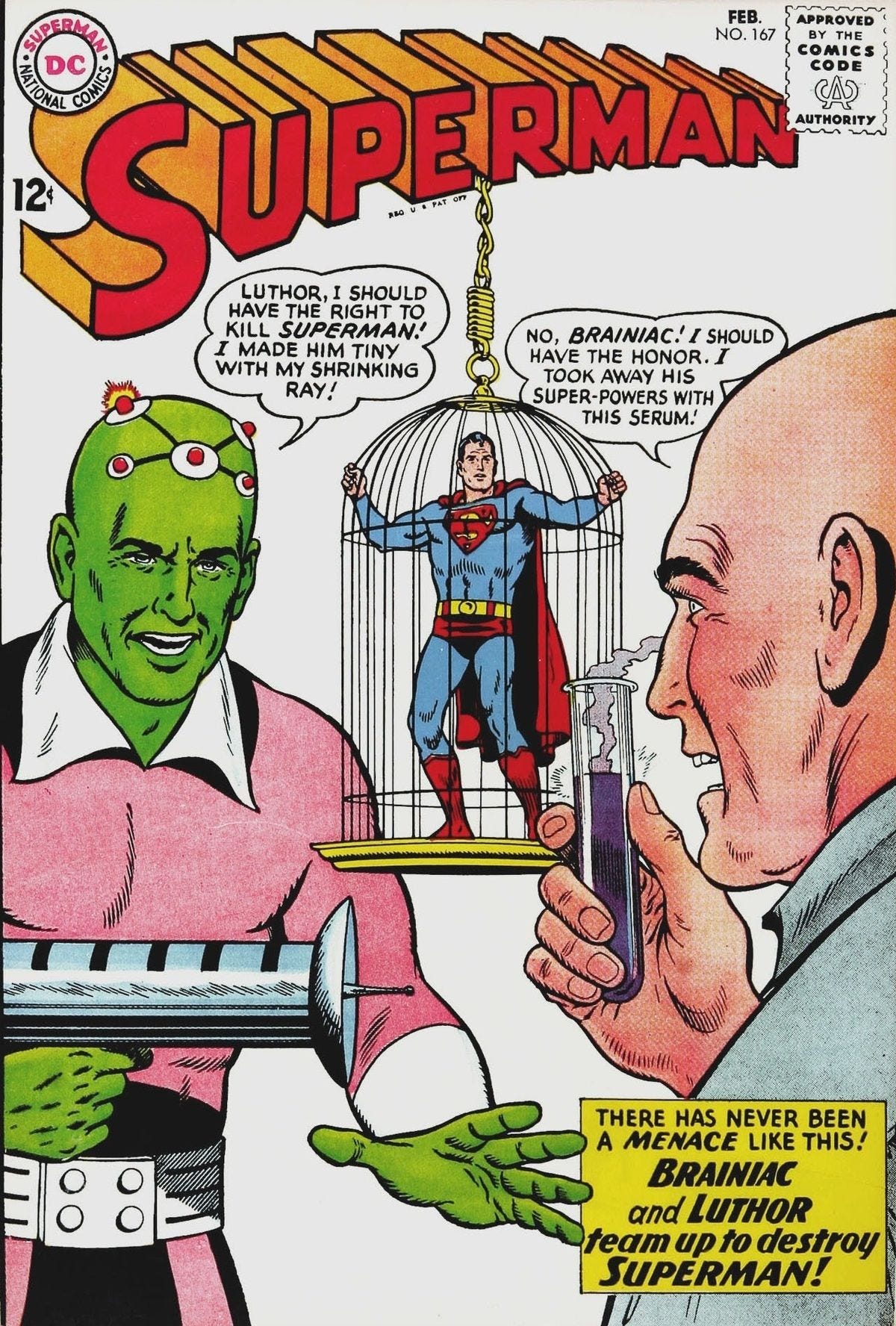

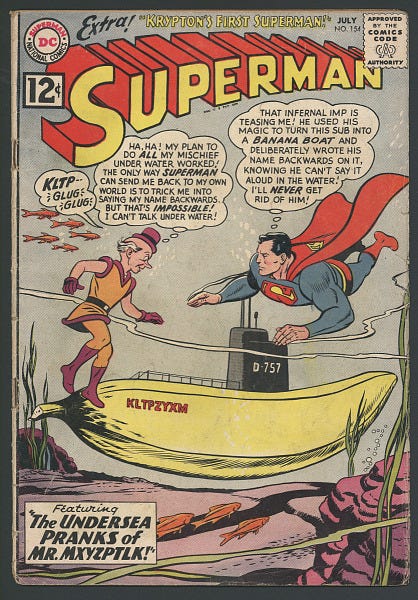

The Parasite was a revolutionary villain for Superman. In the Silver Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, the Big Three Villains for Superman were Lex Luthor, a genius scientist; Brainiac, an alien computer in humanoid form; and Mr. Mxyzptlk, an extra dimensional trickster with magical powers. Luthor and Brainiac posed genuine threats to Superman’s life. Mxyzptlk was really no more than a troublemaker, but never trying to kill him or conquer Earth or do anything really apart from annoying Superman with his pranks.

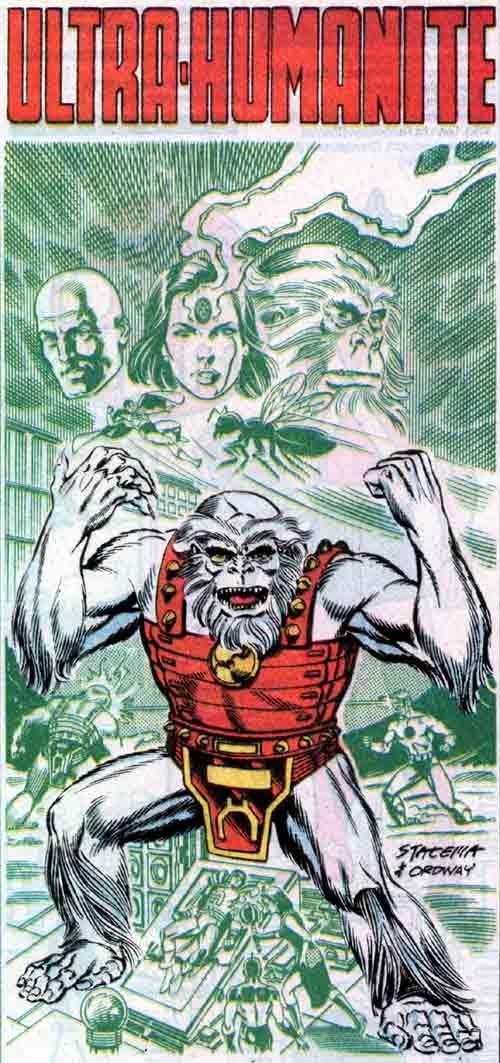

Superman’s first archenemy was the Ultra-Humanite, who debuted in 1939, only a year after Superman’s own first appearance. The Ultra-Humanite was originally a bald, crippled genius scientist, who eventually had his brain transferred into the body of actress Dolores Winters. This was an interesting plot twist, and one may well wonder what the more sophisticated comics writers of later decades might have done with the gender implications here.

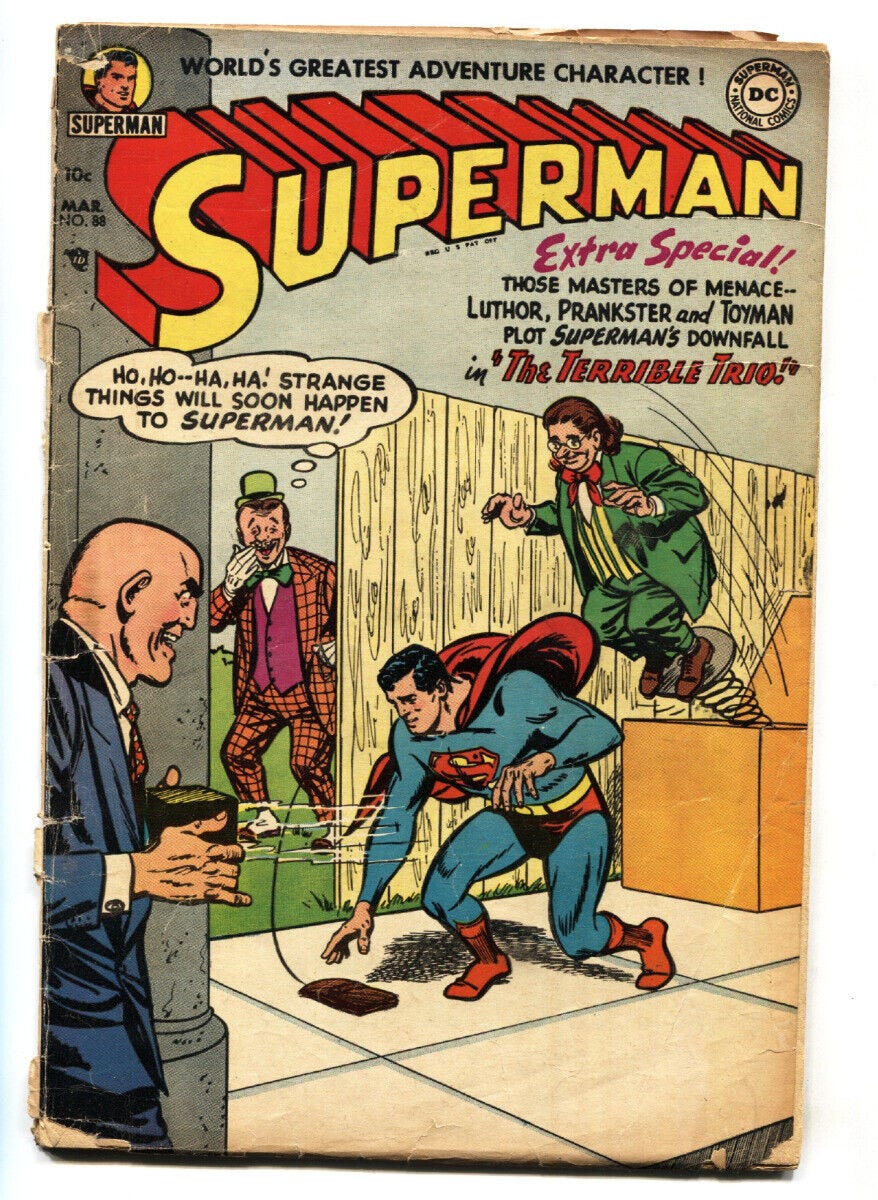

But the Ultra-Humanite disappeared from Golden Age Superman stories, supplanted by another bald scientist, Lex Luthor, who has of course become Superman’s leading foe throughout the rest of his history. The Ultra-Humanite would not reappear until decades later, when his brain was transplanted into a white gorilla. The Big Four Villains for Superman in the 1940s were Luthor, Mxyzptlk, the Toyman and the Prankster. None of the three had super-powers, aside from Luthor temporarily gaining superhuman strength in the “Powerstone” story. Instead, Luthor devised advanced technological weaponry. The Toyman weaponized toys. The Prankster just devised crazy pranks to pull on Superman. As Alan Moore had Superman say in “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?”, the Toyman and the Prankster were really just “nuisances.” Essentially, Mxyzptlk, the Toyman and the Prankster were comedy characters. (In later decades there was a much darker version of the Toyman, and Alan Moore memorably reimagined Mxyzptlk as truly evil in his “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” two-parter, which provided a possible grand finale for the Silver Age Superman continuity.)

What you will note is that none of these villains were physically powerful enough to engage Superman in hand to hand combat. This seems so strange: When you think of Superman, the first of his powers that you think of, even before flying, is super-strength. Yet in the Weisinger stories of the Silver Age, Superman’s greatest foes were trying to outsmart him, not outfight him in physical combat.

Moreover, when you think of Marvel in the Silver Age, you think of dynamic, powerful battle scenes between heroes and villains, and often between heroes, especially as drawn by Jack Kirby.

So in creating the Parasite, Shooter was not only filling a gap, by giving Superman a new opponent who could fight him hand to hand, but was also infusing the staid Weisinger Superman series with Marvel-like energy.

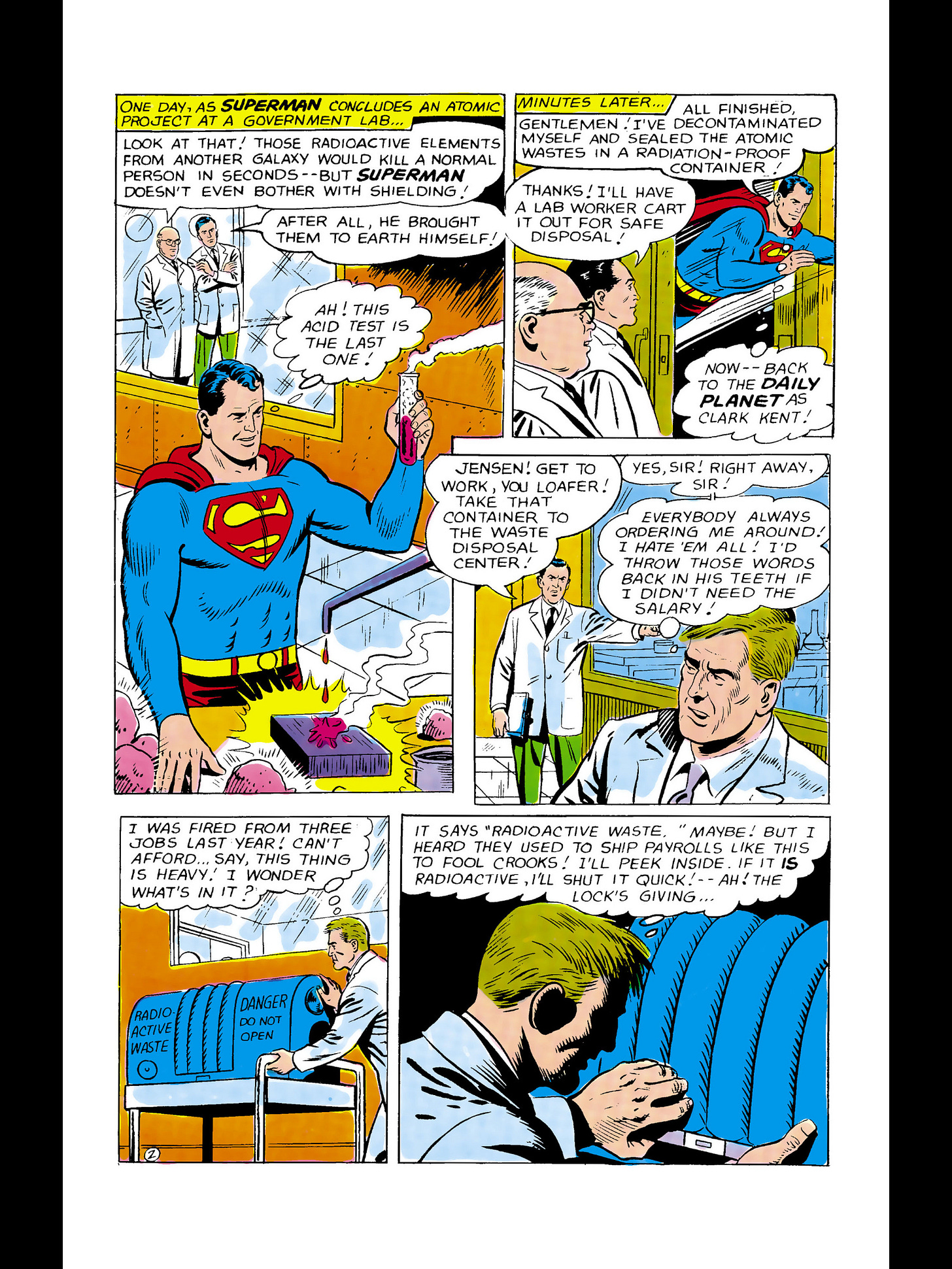

The story opens with Superman performing an experiment in a government laboratory with radioactive materials that he brought from another galaxy. This is a good beginning for various reasons. It gives us Superman at the very start of the story, before he necessarily disappoints for a while so we can see the Parasite’s origin. It shows that Superman benefits humanity in ways apart from battling super-villains and alien invaders: he also helps make scientific advances.

A side note here. One of the paradoxes of superhero stories is that superheroes like Reed Richards or an organization like SHIELD may invent or have access to highly advanced, futuristic technology, but the world at large does not have access to it. The point would appear to be to keep the superheroes in a world that is recognizably our own. Therefore SHIELD, for example, has anti-gravity technology, and so does the Fantastic Four’s foe the Wizard, but not the general public in the Marvel Universe. Sometimes I have wondered if super-villains like the Mirror Master would be more prosperous if they went straight and started companies selling their incredible inventions to the public. Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” is an exception to the rule here, since it shows that Doctor Manhattan is responsible for technological advances on its fictional Earth. But, as the late Peter David was wont to say, I digress.

Yet another clever aspect of this opening panel is that it makes the point that Superman is invulnerable, even to the deadly radiation from these extraterrestrial materials. That will contrast with how the radiation will soon affect the future villain of the story. And the difference between Superman and the Parasite in terms of invulnerability will turn out to be a major theme of the story.

So you can see just from the opening panels how skilled a craftsman Jim Shooter was even in his first year as a comics professional, at age 15!

Shooter then introduces Jensen, a lowly worker at the laboratory who is seething with resentment at his superiors. (His full name would later be established as Raymond Jensen.) He has been fired three times in the previous year. He is clearly a loser who refuses to take blame for his own failings. He reminds me of Joe Meach, the similarly self-deluded failure who became the Composite Superman in a story by Edmond Hamilton that was published two years earlier and that I mentioned in one of my earliest Substack pieces. (I promise that I will eventually return to that story in a future column.) Perhaps Shooter was thinking of Meach. More importantly, Jensen is like a Marvel villain: he is being given a psychological background and a motivation. Meach and Jensen are like the originally unnamed antagonist in Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s “masterwork “This Man, This Monster” in “Fantastic Four” #51: nobodies filled with resentment and envy, unwilling to acknowledge their responsibility for their failures.

Like Meach, Jensen is foolish, letting his ambition get the better of any common sense. Seeing a container marked “radioactive waste,” Jensen recalls rumors that payrolls are transported in containers like this for security reasons (which seems awfully unlikely) and he tells himself that even if there really is radioactive waste inside, a quick peek won’t harm him. He’s being willfully stupid and he’s wrong. (And you might think that a radioactive waste container wouldn’t be so easy to open.)

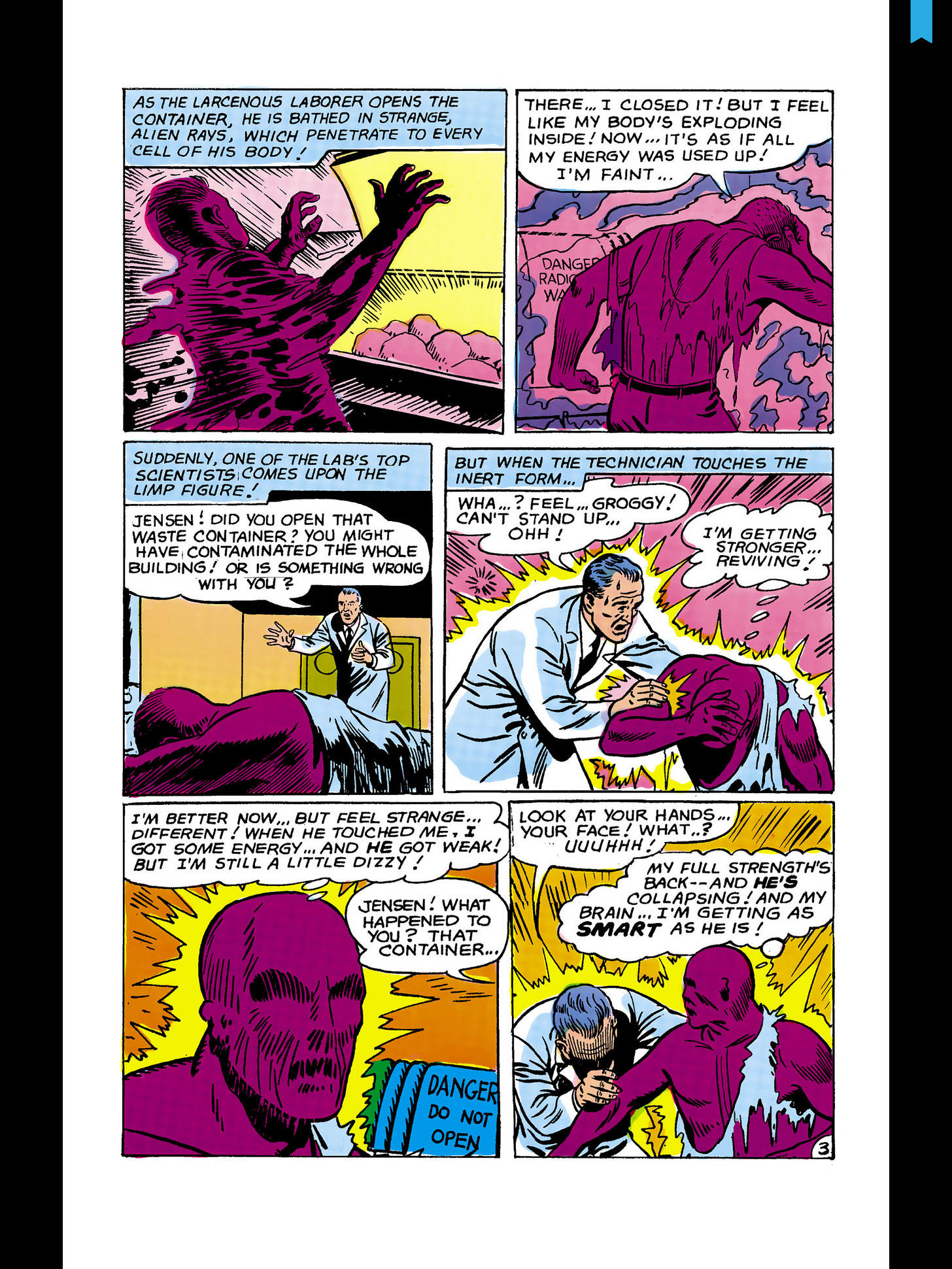

Jensen opens the container and is immediately bathed in radiation, which seems to strike him with explosive force. It’s a horrific sight. This is also very much a Marvel trope: the hero (like Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four and the Hulk) or the villain who is transformed by atomic radiation. The closest Marvel parallel would be laboratory worker Sam Sterns, who is exposed to radioactive waste and is transformed into the Hulk’s archenemy, the Leader, as shown in 1964, two years before this Parasite origin story.

The radiation immediately transforms Jensen into a purple humanoid creature with Superman flies a grotesque face. A laboratory scientist finds Jensen, but when he touches Jensen, Jensen absorbs not only his physical strength but also his intellect, becoming as smart as the scientist. Jensen realizes he has become a superhuman “Parasite,” and that when he absorbs energy from many people at once, he becomes super humanly strong.

I am reminded here of Lee and Kirby’s villain the Absorbing Man, who had debuted a year before. But the emphasis with the Absorbing Man was on his absorbing the properties of whatever material he touched. Shooter’s concept for the Parasite is different and more disturbing: the Parasite drains energy from his victims, thereby not only making himself stronger but weakening his victim. Potentially, the Parasite could drain all of his victim’s life energy, killing him. The Parasite could therefore be seen as a science fiction version of a vampire. I don’t recall ever seeing the Parasite described that way, and under the Comics Code as it existed in 1964, vampires could not be depicted in comics. But that’s what the Parasite essentially is, and that makes this story a synthesis of the superhero genre with the horror genre.

Using his newly heightened intellect to analyze his power, the Parasite realizes that his body has become like an “atomic furnace,” with a metabolism that burns up a normal person’s amount of energy in minutes. So he has to keep draining energy from other people. But, he realizes, if people learn about him and shun him, he will quickly consume all his energy and die.

This, too, seems very much like Marvel to me: the idea that a super-power can also be a curse. It is also an unmistakable Marvel trope that becoming a superhuman can make a person into an outcast, feared and shunned by humanity: Spider-Man (through much of his history), the Hulk and the X-Men are all examples of that.

Next comes a plot twist that is more Weisinger than Marvel: by coincidence Superman flies past Jensen’s apartment window, and the Parasite suddenly becomes much stronger. Well, I suppose in Metropolis people see Superman fly by all the time, though it seems unusual for him to happen to fly so close to Jensen’s window. The Parasite immediately realizes that if he absorbs all of Superman’s energy, he would never run out of power and would become “invulnerable”: in other words, he need no longer fear death. Now this reminds me of Lee and Kirby’s villain Annihilus, who is driven by his obsessive fear of death, and Annihilus did not debut until two years later in 1968!

Moreover, the Parasite realizes that if he absorbed Superman‘s power, he could conquer the world. So there it is: in a single panel the Parasite’s ambition has leapt from survival to world conquest. Like Meach, Jensen is a once powerless nobody and loser who, when granted potentially limitless power, jumps to the opposite extreme: fantasizing about becoming the autocratic ruler of the human race.

The Parasite disguises himself in a hat, coat and other clothes and heads to the site of an announced public appearance by Superman. This isn’t much of a disguise, since his grotesque purple face is fully visible. Similarly, in the early 1960s Lee and Kirby did stories in which the Hulk and Thing walked around anonymously in public, supposedly disguised by hats and coats. But really, are people even in a big city like New York that oblivious?

In another plot twist that seems very much like Weisinger comics of the time, at the site where Superman appeared, the Parasite sees Clark Kent collapse in his presence, feels a surge of superhuman energy, and realizes that Kent is Superman. Thus Shooter heightens the peril for Superman even further: Not only could the Parasite potentially kill Superman, but if he failed to do so, he could still defeat Superman by exposing his secret identity.

A continual theme of Weisinger’s Silver Age Superman stories was Superman’s fear of having his dual identity publicly revealed. Why is this? Why were these stories apparently so popular with readers? One reason, I theorize, is the imposter syndrome: the fear that one is actually a fraud, that Superman really is actually no more than mild-mannered Clark Kent.

The Parasite finally confronts Superman, and as he does so, mentally congratulates himself on his new costume, which he thinks makes himself look more “fearsome.” Actually, it’s not much of a costume, basically just swimming trunks with an odd strip of fabric running up his chest. What makes him look fearsome is his purple physique with his distorted face.

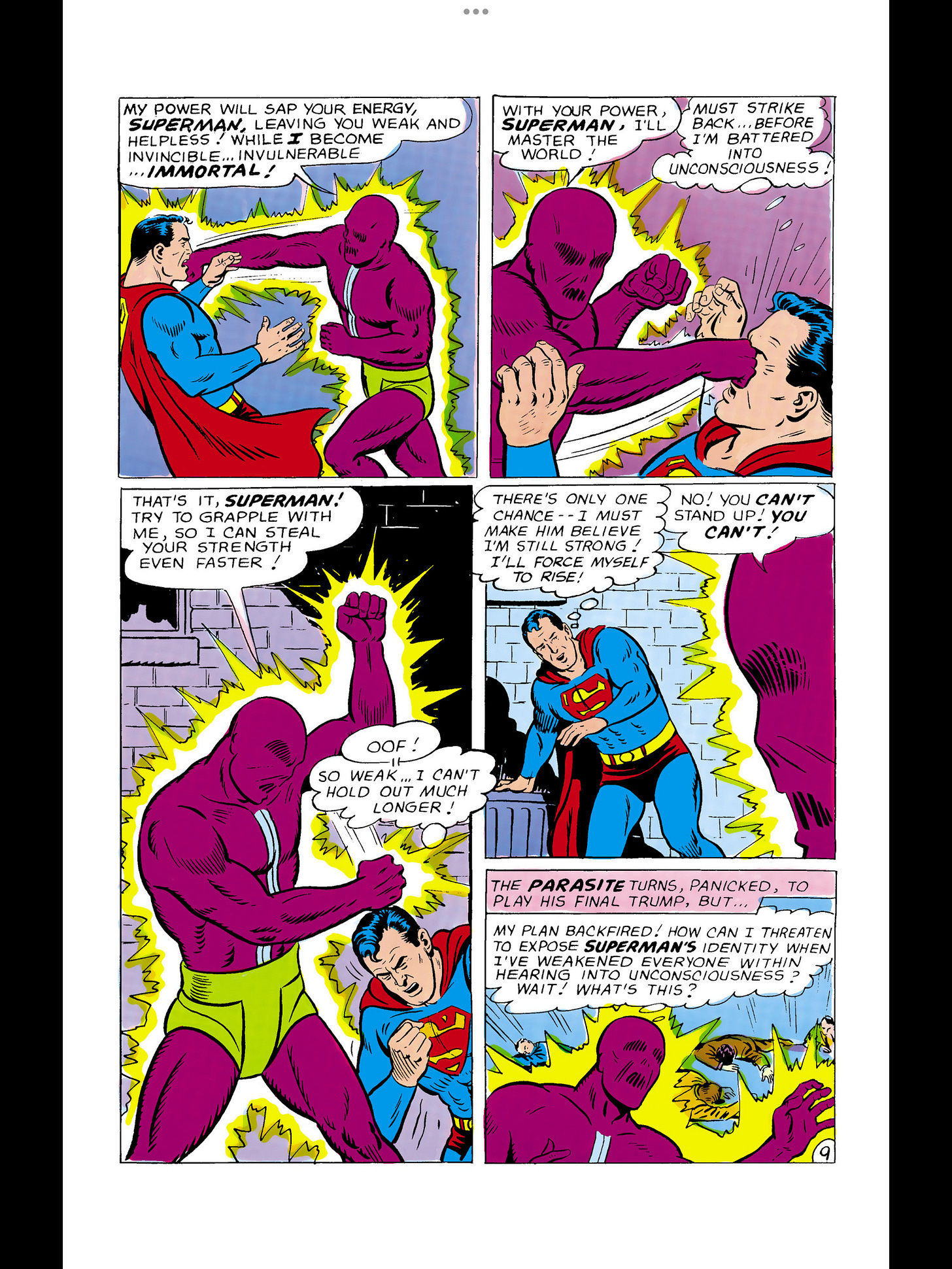

And thus the physical combat between Superman and the Parasite begins. As , it’s powerful hand to hand combat that is part of the Marvel style, and Weisinger’s DC stories needed more of this. However, looking over this fight, it doesn’t look like an equal match. Rapidly weakening from the Parasite’s power drain, Superman seems to be getting the worst of it right from the start. And that reminds me of a continual trope in Weisinger’s 1960s Superman stories, which so often involved Superman losing his powers temporarily, whether through exposure to Red Kryptonite, or to the rays of a red sun, or other means. This presumably reflected another fear felt by the young readership: of losing whatever makes him or her feel important or strong or secure.

The Parasite boasts that by reducing Superman to helplessness, he himself will become “invincible…invulnerable…IMMORTAL!” Again we see that the Parasite is motivated by his fear of his own mortality. In defeating Superman he seeks to defeat death. And that is a sign of hubris, of overreaching, of aspiring to the level of God. Shooter is setting up what will become the moral of this story.

Looking at this story from the perspective of 2025, I am astonished that so much of Superman’s dialogue and the Parasite’s dialogue is in thought balloons. They’re not talking to themselves, which would be unrealistic. Instead, Shooter lets us see into their minds to illuminate their reactions to events, their fears, their plans, and more. Nowadays comics writers and editors avoid the use of thought balloons. Perhaps it’s because they see comics in cinematic terms, and think that thought balloons, and for that matter narrator captions, are dated and uncinematic. But the thought balloon is a perfectly good tool in the comics medium, and comics creators should employ the tools that the medium affords them. This story is a fine example of how to use thought balloons well to illuminate characterization and even to build suspense as we see how the characters react to the building dangers.

As the battle continues, Shooter shows us Superman’s courage as he continually struggles against seemingly overwhelming odds, and, perhaps unexpectedly, the Parasite’s growing bewilderment, panic and desperation at Superman’s refusal to be defeated.

But finally Superman lies defeated. The Parasite boasts that Superman is on the brink of death, and now breaks through the final barrier of Superman’s invulnerability, invading his mind and thoughts. “Superman’s innermost secrets stream into the Parasite’s brain.” Imagine that happening to you: your innermost secrets laid bare. You would have lost everything. It’s like a psychic rape.

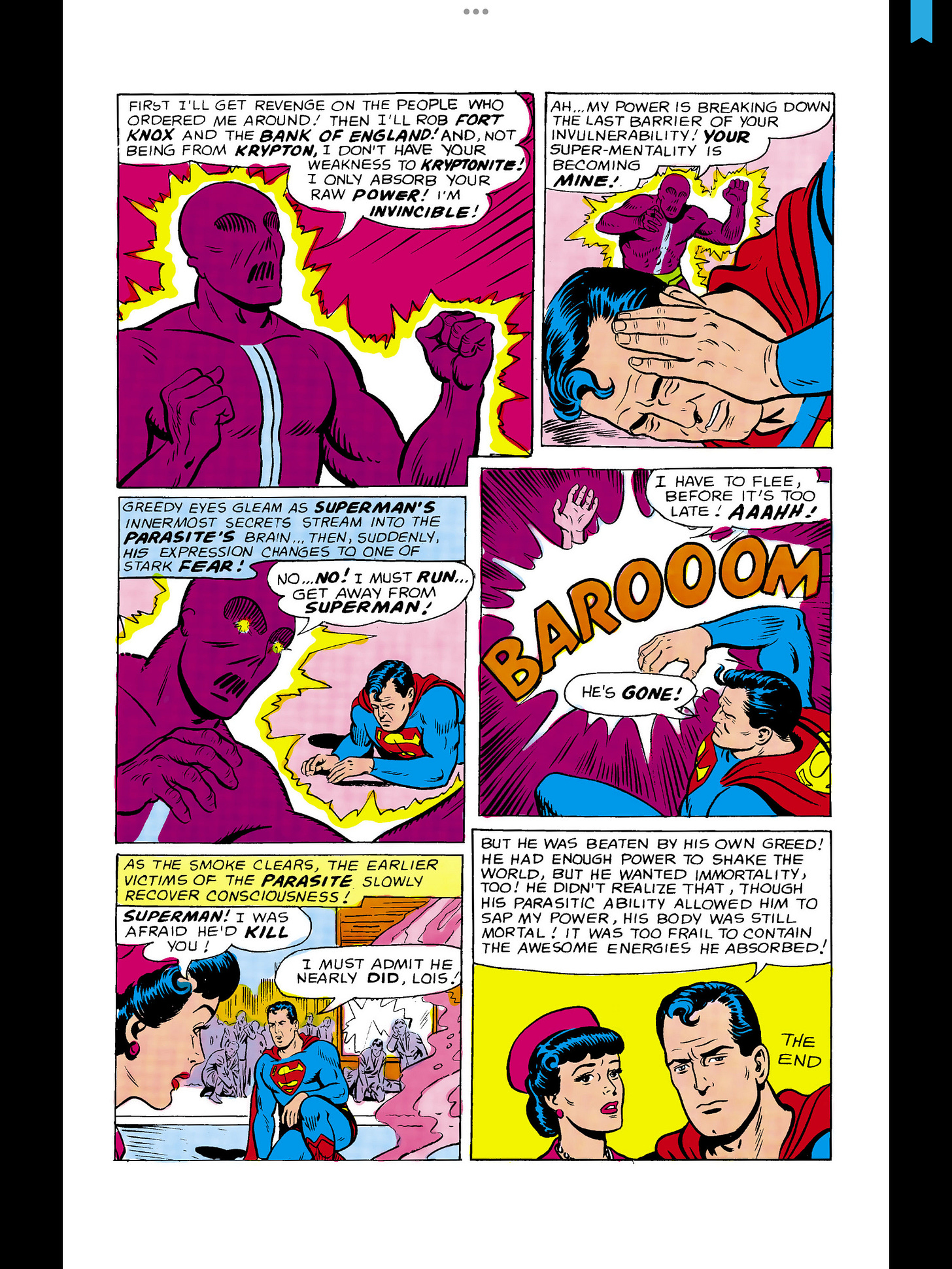

And then, abruptly, everything changes. The Parasite becomes absolutely terrified, and then he explodes, vanishing seemingly into vapor.

What happened? Since he was reading Superman’s mind, did he learn something that horrified him? I would guess that Superman knew that the Parasite was bringing about his own demise, and how, and that the Parasite was aghast at learning this, and realizing he was seconds away from death.

In the final panel Superman explains to Lois Lane what just happened. This was indeed a tale of hubris. Unsatisfied with becoming the most powerful being on Earth, the Parasite “wanted immortality, too,” Superman says. But, he continues, “his body was still mortal. It was too frail to contain the awesome energies it absorbed.”

I don’t know if this ending makes sense. Superman isn’t immortal, either. And wasn’t the Parasite absorbing the yellow sun energy that makes Superman invulnerable, too? The Parasite would have to have a measure of invulnerability to withstand Superman‘s fists in their battle, and to prevent his own fists from shattering on hitting Superman’s virtually indestructible body.

Nonetheless, this ending feels right. Jensen was an unworthy mortal who sought to steal godlike power but was destroyed by it.

It seems that Shooter intended this to be the Parasite’s one and only story. But a year or so later Shooter wrote a sequel, finding a way to resurrect the Parasite. Shooter had created an important new addition to Superman’s rogues gallery. Various versions of the Parasite have appeared in comics and in animation in the many decades since.

This was such a triumph for Jim Shooter, only 15, in his first year as a professional comics writer. As noted, it showed him infusing the lessons he had learned from studying Marvel stories to DC Universe stories, and thus foreshadowed his work as editor in chief overseeing Marvel’s own comics. It’s too bad that DC’s other Silver Age writers, all much older than Shooter, did not follow his example, with the exception of Arnold Drake, whose work on “Doom Patrol” also paralleled Marvel characterization and fight dynamics. The new generation of comics writers, Shooter’s generation, who grew up reading comics in the 1960s absorbed the lessons of the Marvel style of superhero storytelling and applied them in their own work. In the 1970s and 1980s DC superhero stories increasingly became like Marvel’s, and many writers of the new generation worked at both companies. In 1986 writer and artist John Byrne rebooted the Superman mythos in his comics miniseries “The Man of Steel,” which in art, story and characterization was thoroughly Marvelized. And ironically, Byrne had left Marvel for DC in large part because he, like other creators, was dissatisfied with Shooter’s micromanagement as editor in chief. But as I said at the start, that is a topic for another time.